→

HISTORY

↓

The history of the Kerma region is unique and rich. The remains of its glorious past are accessible today, thanks to the work of enlightened amateurs and passionate archaeologists.

LOCATION

Kerma, the capital of the first kingdom of Sub-Saharan Africa, is located in the heart of Sudanese Nubia.

Nubia is a vast region located in northern Sudan and southern Egypt, between the First and the Fifth cataracts. South of the Second Cataract, numerous rock outcrops, which give the area its rugged terrain and make access difficult, have limited the movement of populations. In fact, this area is called the ”belly of the stones” because it was a natural boundary that impeded contact between the Nubians and the Egyptians.

The Kerma region is in the centre of Nubia, a few kilometres upstream from the Third Cataract. This strategic location allows for the control of communications along the Nile Valley; it opens onto the largest alluvial plain of northern Sudan (15 to 20 km wide along 200 km). These natural conditions played an important role in the region’s population dynamics and explain, in part, its archaeological wealth, during prehistoric and historical periods.

→

Chronology

↓

| PERIODS | DATES | SITES |

|---|---|---|

| Contemporary Period | 1956- Today |

Independence and establishment of the Republic of Sudan |

| Colonial Period | 1896—1953 | Anglo-Egyptian treaty establishing condominium over the Sudan |

| Islamic Period | 1317-1885 | Forced conversion of the Kingdom of Dongola to Islam Incorporation into the Ottoman Empire |

| Mediaeval Period | 640-1323 | Christian kingdom of Makuria |

| Post-Meroitic Period |

400-600 | Several regional powers |

| Meroitic Period | 400 B.C. - 400 A.D. | Political centre moved to Meroe Continuation of constructions at Tabo and Dukki Gel Occupation of the western cemetery |

| Napatan period | 730-400 | Kings from Napata Restorations and constructions at Dukki Gel and Tabo Expansion of the western cemetery at Kerma |

| Nubian Pharaohs | 713-656 | Twenty-fifth Dynasty rules over a territory encompassing Egypt and Sudan |

| Dark Ages | 1080-730 | Withdrawal of Egyptian authority. Period poorly documented |

| Egyptian Occupation | 1480-1080 | Conquest of Nubia by Egyptian pharaohs of the New Kingdom Destruction of the city of Kerma and foundation of Dukki Gel |

| Classic Kerma | 1750-1480 | Expansion of the city and the defence system. Temples (deffufa) and royal tombs. |

| Middle Kerma | 2050-1750 | Erection of fortified walls. Palaces and princely tombs. |

| Early Kerma | 2450-2050 | Foundation of the city Development of the religious quarter and the eastern necropolis |

| Pre-Kerma | 3200-2500 | Several settlements, including a proto-urban agglomeration on the site of the eastern necropolis |

| Neolithic | 4700-4300 5000-4000 6000-5500 7200-6500 |

First villages of stock breeders on the site of the eastern necropolis Cemeteries at Kadruka Cemeteries at el-Barga Settlements and tombs at Wadi el-Arab |

| Epipalaeolithic | 7500-7000 8300-7800 |

Settlements and cemeteries at el-Barga Settlements at Busharia |

| Middle Palaeolithic | 200,000-35,000 | Evidence of occupation and knapping workshops at the summit of volcanoes |

| Acheulian | 500,000-200,000 | Evidence of occupation |

| Lower Palaeolithic | 1,000,000-500,000 | Camp remains at Kaddanarti and Kabrinarti |

-

Periods

Contemporary period

-

dating

1956—Today

-

Site

Independence and establishment of the Republic of the Sudan

-

Periods

Colonial period

-

dating

1896—1953

-

Sites

Anglo-Egyptian treaty establishing a condominium over the Sudan

-

Periods

Islamic era

-

dating

1956—Today

-

sites

Forced conversion of the kingdom of Dongola to Islam

Incorporation into the Ottoman Empire

-

Periods

Meroitic period

-

dating

400 BC AD - 400 AD. J.-C.

-

sites

Transfer of the political center to Meroe

Continuation of construction in Tabo and Doukki Gel

Occupation of the western cemetery

-

Periods

Napatan period

-

dating

730-400

-

sites

Sovereigns from Napata

Restorations and constructions in Doukki Gel and Tabo

Extension of the western cemetery in Kerma

-

Periods

Nubian pharaohs

-

dating

713-656

-

sites

XXV Dynasty reigning over the whole territory of Egypt and Sudan

-

Periods

Dark ages

-

dating

1080-730

-

sites

Loss of Egyptian grip. Poorly documented period

-

Periods

Egyptian occupation

-

dating

1480-1080

-

sites

Conquest of Nubia by the Egyptian pharaohs of the New Kingdom

Destruction of the city of Kerma and foundation of Doukki Gel

-

Periods

Classic Kerma

-

dating

1750-1480

-

sites

City and system expansion

Defensive. Temples (Deffufa) and royal tombs

-

Periods

Elder Kerma

-

dating

2450-2050

-

sites

City foundation

Development of the religious district and the eastern necropolis

-

Periods

Pre-Kerma period

-

dating

3200-2500

-

sites

City foundation

Several establishments including a proto-urban agglomeration at the location of the eastern necropolis

-

Periods

Neolithic

-

dating

4700-4300

-

sites

First pastoralist villages on the site of the eastern necropolis

-

dating

5000-4000

-

sites

Cemeteries in Kadruka

-

dating

6000-5500

-

sites

Cemetery in El-Barga

-

dating

7200-6500

-

sites

Habitats and tombs in Wadi El-Arab

-

Periods

Epipaleolithic

-

dating

7500-7000

-

sites

Habitats and cemeteries in El-Barga

-

dating

8300-7800

-

sites

Habitats in Boucharia

Prehistory of the Region

The global evolution of human populations in the Kerma region is attested for almost one million years.

The history of the human population of this part of Upper Nubia is evidently punctuated by undocumented periods. However, recent research has allowed a more refined understanding of the millennia preceding the birth of the first kingdom of sub-Saharan Africa.

The first evidence of settlement in the region is found at the site of Kaddanarti. The site is a camp marked by the presence of flint tools (mostly choppers and chopping tools) and now-gone animal bones. It dates back to between one million and half a million years ago. Although the people of this epoch walked on two legs and made tools, they do not correspond to the definition of modern man. As suggested by discoveries made in Ethiopia, Kenya and Chad, the region might have been inhabited during an even more ancient period.

Surveys conducted during the last few years have led to the identification of more recent sites dated to the Acheulian period (between 500,000 and 200,000 B.C.) and particularly to the Middle Palaeolithic (between 200,000 and 35,000 B.C.). The most spectacular deposit is found at the summit of an ancient volcano, 40 km from the Nile. Knapping workshops, flakes, and basalt tools are found today in the place where they were abandoned several tens of thousand of years ago.

During the Upper Palaeolithic (between 35,000 and 10,000 B.C.), the climate became particularly arid and this period is not attested in the region. Human populations were probably forced to move closer to the Nile and the remains of their presence are today found buried under several metres of sediments or were swept away by the floods.

The Epipalaeolithic (between 10,000 and 7000 B.C.) is a well-documented period. Climatic variations during the Holocene have greatly influenced human population. Between 10,000 and 6000 B.C., increased humidity promotes the formation of lakes in the Sahara and of abundant savannah-like vegetation. The majority of now-arid areas were in those days inhabitable, which facilitated contacts throughout the Sahara along an east-west axis. On the other hand, the banks of the Nile were difficult to reach and populations chose to settle away from the floodplain.

At the onset of the fifth millennium, the beginning of an arid phase causes people to move closer to the river and settle in the Nile Valley. Nowadays, it is possible to highlight the main social and economic transformations that took place through the millennia and that led to the development of a powerful kingdom dominating the region: sedentary lifestyle, livestock farming, agriculture, trade development, population growth, social disparity and the birth of the first cities.

For further information:

Read the publications of M. Honegger.

Archaeological sites :

PRE-KERMA

Pre-Kerma develops between the end of the fourth and the beginning fo the third millennium B.C. It bears witness to an important social complexification, foreshadowing the formation of the first kingdom of Sub-Saharan Africa.

The period that covers the fourth and third millennia is ill known in the Kerma region. The gradual aridification of the climate causes populations to move towards the banks of the Nile. The remains of their settlements, now located in the cultivation zones, were mostly destroyed during the ploughing of the fields. Although rare, evidence does exist; it is noted at the site of the eastern necropolis, where a vast agglomeration was revealed under the tumuli of the Kerma period.

This agglomeration, discovered in the mid-1980s, covers one and half hectares, and corresponds to the permanent settlement of an agro-pastoral community. It comprises approximately 40 huts measuring between four and seven metres in diameter, which surround a storage area that includes almost 500 cereal granaries. Three buildings are noted for their rectangular shape. These appear to have served an administrative, religious or defensive function rather than a domestic one. Large animal pens delineated by wooden palisades and imposing fortifications developed on the outskirts of the settlement.

These constructions already denote a certain degree of densification and complexification of the settlement, which in turn represent the emergence of a more complex society. Thus the Pre-Kerma people who settle along the Nile between 3500 and 2500 B.C. seek protection from outside threats and wish to safeguard their wealth within a vast and completely enclosed complex that must have covered tens of hectares.

Archaeological data pertaining to this period are rather rare in Upper Nubia and it is rather difficult to highlight connections between Pre-Kerma people and their neighbours. We only know that contacts deepen throughout the Nile Valley and that Nubia’s riches—notably gold, ivory, ebony and cattle—are coveted by elites in the north. Trade increases between Lower Nubia, occupied by the A-Group, and Upper Egypt. Upper Nubia was undoubtedly influenced by these interactions, but it remains difficult to ascertain its implication in Nilotic trade. At the moment, because of the few Pre-Kerma settlement sites and the rarity of necropoleis, it is impossible to formulate a firm idea regarding the dynamism of this culture in the region.

For further information:

Read the publications of M. Honegger.

Archaeological site :

Pre-Kerma Agglomeration, in the middle of the Kerma necropolis

KINGDOM OF KERMA

The Kingdom of Kerma, a Nubian culture that emerged late in the fourth millennium B.C., will dominate Upper Nubia for almost a thousand years.

Kerma owes its name to the modern city located south of the Third Cataract, on the east bank of the Nile, where are found the most important remains of this civilisation: the kingdom’s capital and its eastern necropolis. Two imposing sites, these span between 2500 and 1500 B.C. American scholar George A. Reisner, known as the father of Sudanese archaeology, discovered during his excavations (1913-1916) the remains of a unique culture. Since then, numerous other sites located between the First and Fifth cataracts have yielded important information regarding this culture. Nonetheless, the most important site remains that of Kerma itself, the capital of the kingdom, with its city and necropolis.

In the Kingdom of Kerma, writing is unknown; Egyptian texts refer to it as Kush. Its inhabitants prospered by livestock farming (bovines and caprines), exploiting of vegetable resources as well as hunting and fishing. Trade (gold, precious stones, ivory, animal hide, ebony, cattle) also contributed to the city’s wealth, due to its location in the centre of a fertile basin and at the crossroads of desert routes linking Egypt, the Red Sea and the heart of Africa. The Nubians, known to be shrewd warriors and talented archers, cared to protect themselves from enemy raids. They built trenches, palisades and fairly strong enclosure walls with numerous bastions.

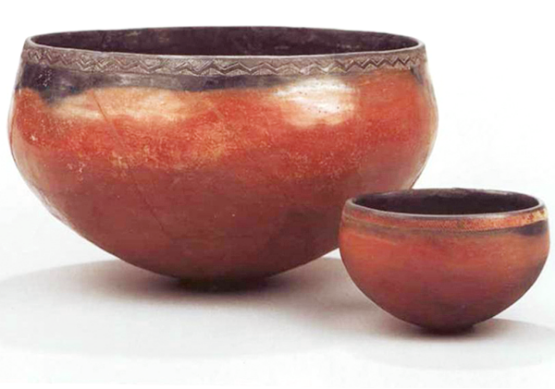

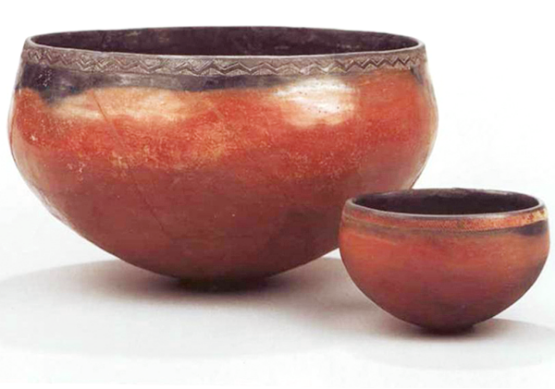

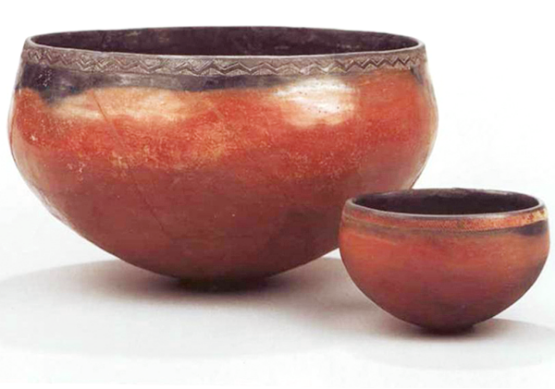

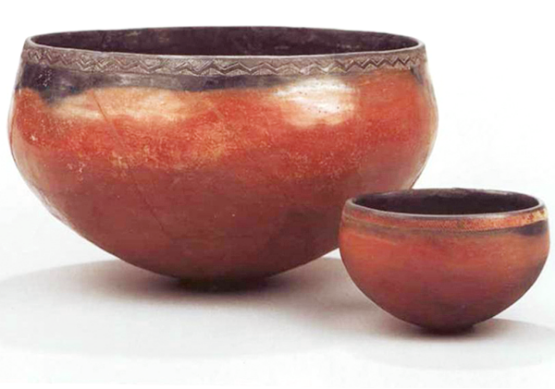

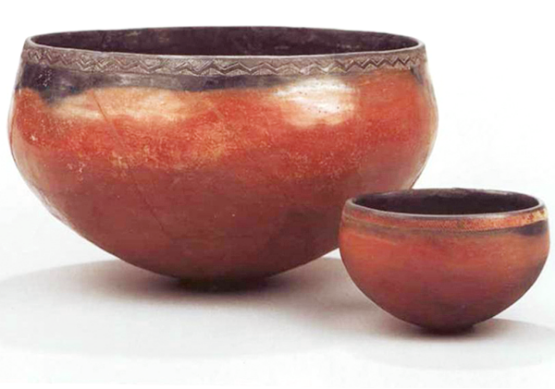

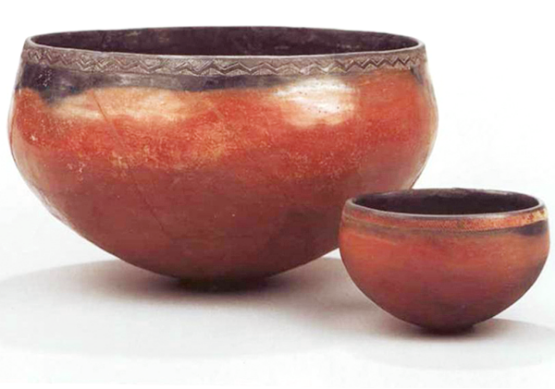

Based on ceramic materials discovered in the cemeteries on Sai Island and at Kerma, three chronological periods can be distinguished: Early Kerma (circa 2450-2050 B.C.), Middle Kerma (circa 2050-1750 B.C.) and Classic Kerma (circa 1750-1480 B.C.). A fourth period, called Final Kerma, denotes the transition between the end of the kingdom and the Egyptian occupation (circa 1480-1450 B.C.).

Classic Kerma is the most glorious period the kingdom has known. The influence of its rulers spreads even to Lower Nubia and an alliance proposed by a Hyksos king of the Fifteenth Dynasty, around 1580 B.C., corroborates the kingdom’s importance on the political scene. Monumental and large-scale works are undertaken in the city and the necropolis. The western deffufa now resembles an Egyptian temple and a port is established south of the city. Two large temples of more than 40 m tall are erected in the necropolis, where the last royal tumuli clearly demonstrate the power of the kings. The kingdom’s collapse is undoubtedly hastened by this conspicuous display of wealth, coveted by northern neighbours, as well as the overexploitation of soils and an increased desertification.

Egyptian Occupation

The city of Dukki Gel is founded by the pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

The Egyptian conquest of the Kingdom of Kush is carried out by one of the most illustrious New Kingdom pharaohs, Thutmosis I (1496-1483 B.C.). After having recaptured the forts of Lower Nubia and seized Kerma, he establishes a new city one kilometre north of the latter, at the site of Dukki Gel. Egyptian influence over this region south of the Third Cataract is not truly felt until the reign of Thutmosis III (1479-1424 B.C.).

The Nubians must leave their homes, often burnt during the conquest. Several settle at Soleb, Sesebi, Tabo, Kawa or at the foot of Gebel Barkal. Our understanding of the transition from the Kerma cultures to the Egyptian occupation is made difficult due to numerous conflicts between indigenous populations and the new settlers. The administration of the country is given to a viceroy, who bears the title “King’s Son of Kush,” although a certain authority is left to the local elite. Indeed, a policy of Egyptianisation is quickly launched. The children of the defeated chiefs are thus sent to Egypt in order to be educated in Pharaoh’s court.

Today, the city of Dukki Gel is partially buried under a palm grove, which makes impossible an exhaustive study of its development. Available landmarks, however, allow a comparison of its proportions to other Egyptian cities in Nubia. Interpretation of the religious quarter proves complex; our understanding of early buildings is complicated by restorations and constructions dated to the later Napatan or Meroitic periods. Projects commissioned by pharaohs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth dynasties are evidenced by the various foundation deposits discovered at temples within the precinct. One of these temples was dedicated to the god Amun.

The city’s enclosure wall is abandoned in stages at the end of the Ramesside period (around the 11th century B.C.). Egypt, more preoccupied with the Mediterranean, loses control of Nubia. For the next three centuries, the history of Middle and Upper Nubia is obscure. Nubian history shines again with the emergence of a monarchy from the Napatan region, upstream from the Fourth Cataract.

For further information:

Read the publications of C. Bonnet.

Archaeological site :

Napata and Meroe

During its long history (spanning from 8th century B.C. to the 4th century A.D.), the Kingdom of Kush is divided into two periods—the Napatan and Meroitic periods—based on the location of the kingdom’s nerve centre.

During the 8th and 7th century B.C., Nubia experiences an extraordinary renaissance, under the impetus of powerful kings established in the Fourth Cataract region. Not only will they reclaim control over their ancestral lands, they will conquer Egypt. Around 730 B.C., Piankhy (also known as Piye), king of Napata, undertakes the pacification of Egypt, then prey to internal turmoil and Assyrian threats. He unifies the north and the south and thus establishes the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, often called the “Ethiopian” or Kushite dynasty. His successors reign over a vast empire spreading from the Egyptian Delta to the confluence of the Blue and White Niles for almost sixty years, from 713 to 656 B.C. These sovereigns of the Two Lands wear as symbol of their double royalty a diadem graced with two cobra-uraei.

Henceforth, kings are buried under pyramids, placed under the protection of the god Amun and use the Egyptian language, an obvious demonstration of Egyptianisation. Nonetheless, the place given the god Amun within Kushite religion is somewhat surprising, considering that he is worshipped in the form of a ram, an animal that played an important role in the Kerma culture. Monumental architectural projects are attributed to these pharaohs, whether in Egypt or in Sudan, like at Gebel Barkal, Sanam, Kawa or Tabo. The capital city is moved for strategic and religious reason from Kerma to Napata, at the foot of Gebel Barkal, the birthplace of the god Amun. Finally, the Kushite Dynasty falls under repeated assaults by the Assyrians and the kings of the Delta. During an expedition to Nubia under Psamtik II, the Egyptians try to eradicate all traces of these “black pharaohs.” Among other things, they destroy the royal statues erected in temples, the remains of which were found at Gebel Barkal at the onset of the 20th century and at Dukki Gel in 2003. In the aftermath of this expedition, the Kushite kings regain control over Nubia as the Kingdom of Napata, but they do not extend their power downstream from the Second Cataract.

During the 4th century B.C., the Nubian kings, concerned with threatening Egyptian armies and later with the Ptolemies and the Romans, decide to move their political centre to Meroe, south of the Fifth Cataract. This new location offers important strategic and economic benefits because the region is blessed with abundant rains and is located within a network of trade routes. Thus Meroe becomes the capital of a prosperous empire, its culture traditionally Nubian, but with a level of Egyptianisation among the elite.

This historiographic distinction between the “Kingdom of Napata” and the “Kingdom of Meroe” is rather arbitrary considering the cultural and political continuity between them. Moreover, it is difficult to analyse its evolution; while Meroitic writing has been deciphered, the language has yet to be understood.

For further information:

Read the publications of C. Bonnet.